After just discussing the importance of setting in a book, I’ll move on to one of those stories with no particular setting whatsoever. “The Elephant and the Bad Baby” by Elfrida Vipont and illustrated by Raymond Briggs (of “The Snowman” fame) is one of those simple premises that creates a satisfying read-aloud story, built on rhythm and understanding of what makes children want to join in.

The plot is wonderfully straightforward: an elephant meets a baby, offers him a ride, and they proceed to go “rumpeta, rumpeta, rumpeta, all down the road” while acquiring food from various shops without paying. Ice cream, meat pies, buns, gingersnaps (or crisps if you’re reading the original British version), cookies (or biscuits), lollipops, apples - the list grows as the irate shopkeepers chase behind in an increasingly frantic parade. It’s a cumulative tale in the finest tradition, building momentum with each addition until the inevitable resolution.

What makes the book a favorite for me isn’t the story, but rather the telling of it. Vipont understood that cumulative tales live or die on their rhythm, and she created language that demands to be read aloud. The pattern is hypnotic: the elephant asks the bad baby if he would like a treat, the bad baby says yes, the elephant gets one for each of them, and then rumpeta rumpeta with yet another angry shopkeeper joining the chase. “Rumpeta, rumpeta, rumpeta” becomes the drumbeat that carries the whole adventure, while the growing parade of pursuers builds a cumulative tension.

This is children’s literature that acknowledges its oral tradition. These words aren’t meant to be read silently, they’re meant to be performed, chanted, and shared. The rhythm is so strong that once you’ve read the book a few times, you’ll find yourself unable to deviate from its cadence. Children sense this and often begin anticipating the repetitions, joining in with their own “rumpetas” or predicting what the elephant will offer next.

We never see much evidence of what makes the titular “bad baby” bad - we’re simply told he’s a bad baby. The baby never asks or demands treats; the elephant offers a ride and food with generous spontaneity, and the bad baby simply accepts. Their adventure has the logic of play rather than genuine misbehavior. If this is badness, it’s the most passive kind imaginable - that delicious sort of rule-bending that feels consequence-free. The only concrete “fault” emerges towards the end when the elephant suddenly realizes that the bad baby has never once said please, but even this feels more like an oversight than genuine rudeness, as the elephant was the one offering items not belonging to him.

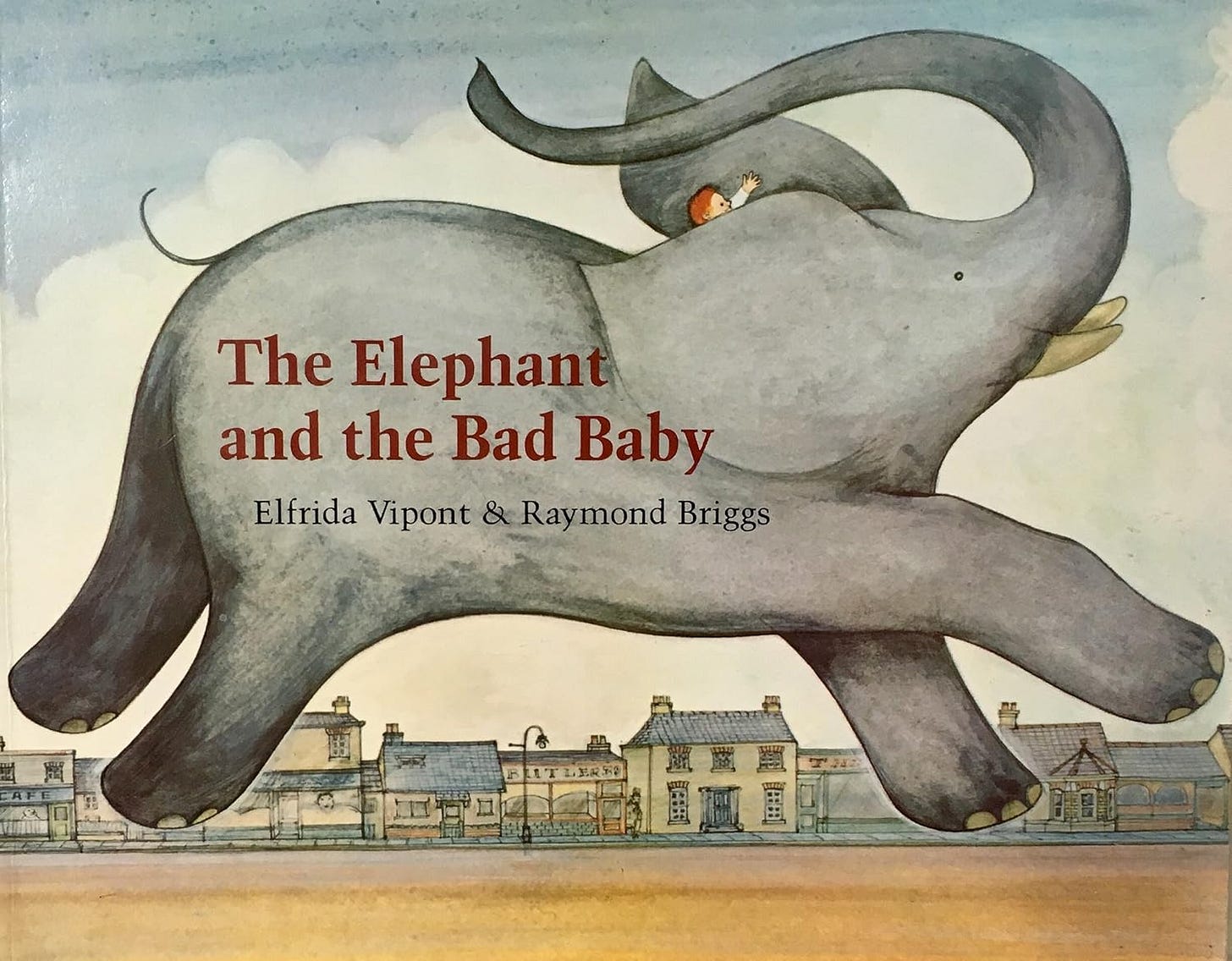

Raymond Briggs’ illustrations support the story perfectly. His elephant is both magnificent and approachable, large enough to be impressive but gentle enough to be trustworthy with a baby. The baby himself is appealingly round and mischievous without being mean-spirited. The growing crowd of angry shopkeepers is more comic than threatening, their indignation more silly than serious.

Briggs brings his distinctive style to the story - the same warmth and humanity that would later make “The Snowman” a much beloved holiday classic (this deserves its own discussion come December). His ability to make fantastical scenarios feel grounded and emotionally authentic serves this cumulative tale perfectly.

The resolution is equally sweet in its simplicity. The elephant’s sudden realization about the lack of gratitude from the bad baby, and the shopkeepers all aghast at this revelation (rather than being aghast at the elephant’s thievery). The baby’s mother appears at the end, not scolding or demanding an explanation - she simply asks if everyone would like some supper (or tea, if you’re in the original British version) and makes pancakes for the lot of them. The shopkeepers, elephant, and the bad baby all sit down together for a meal that transforms a wild chase into a calm, community gathering. But the real ending comes after the meal, when the bad baby goes to bed and all the shopkeepers get up and chase after the elephant alone (still going “rumpeta rumpeta rumpeta” all down the road), without the bad baby.

This ending makes the entire adventure feel potentially dreamlike. The cycle begins anew, the adults now playing the children’s game, the rhythm continuing without the original catalyst of the bad baby - it all has a rather fluid, circular quality of a child’s fantasy, where the adventures never really end, but instead transform into new versions of themselves.

This ending works because it doesn’t punish the adventure or impose heavy lessons. The shopkeepers, who have been scolding throughout the chase, suddenly join the playful logic themselves and sit down to eat pancakes together, forgetting their shops. Interestingly, the mother herself is barely a character, but perhaps that's the point - she doesn't need development because she represents that foundational security children take for granted. As soon as the adventure turns slightly uncomfortable (being told he never said please), the bad baby naturally returns to the person who will make everything better without question. Her immediate offer of pancakes to everyone isn't wisdom or strategy - it's simply the unconditional generosity that secure children expect from their mothers.

The book also demonstrates something important about repetition in children's literature. Adults often worry that repetitive texts are boring or too simple, but children understand that repetition serves different purposes than novelty. The repeated phrases and cumulative structure in "The Elephant and the Bad Baby" create security - children know what's coming and can participate in the telling.

This same appeal explains why cumulative books like "This Is the House That Jack Built" become beloved by children while driving parents to distraction. My toddler adores the endless building and rebuilding of that rhyme, while my husband finds it maddening. But cumulative stories serve children's developmental needs, building memory skills and providing the satisfaction of anticipated patterns. The growing complexity challenges them just enough while the repetition provides comfort.

More importantly, the rhythm and repetition make the book memorable in ways that more complex plots often aren't. Children who hear this story a few times can often retell it themselves, carrying the language with them long after the book is closed. My toddler now says "rumpeta rumpeta rumpeta" when you ask her what an elephant says - evidence of how deeply these rhythmic phrases embed themselves in children's language play. This is literature that becomes part of a child's internal repertoire, joining the folk songs and nursery rhymes that form the foundation of linguistic development.

"The Elephant and the Bad Baby" reminds us that some of the best children's books work like good folk songs - simple on the surface, sophisticated in their understanding of rhythm and repetition, and designed to be shared rather than consumed alone. In our current landscape of children's books designed to teach specific lessons or showcase particular values, this story succeeds by focusing on pure narrative pleasure and the joy of language itself.

It's also a book that bridges cultures and generations effortlessly. The specific shops and foods might be British, but the core experience - a magical friend, a spontaneous adventure, the satisfaction of repetitive language - translates across time and place. Children everywhere understand the appeal of consequence-free mischief and the comfort of rhythmic storytelling.

Next week: A meadow, a child, and the patient art of making friends - when children's books see the world through truly young eyes.

A minor point jumping off from these lovely observations: THIS is the kind of children's book in which I most want representation! In which the minority status of the character is of minor value to the story, and my white children can easily learn to relate to protagonists that don't look like them.

Is it the most important? No, certainly not, but it does seem to be the hardest to find.