Most children’s books feel as though they could happen anywhere. Generic suburban houses, nameless towns, settings that exist mainly to provide backdrop for whatever lesson or adventure the author has in mind. And then there’s Katie Morag, who lives so specifically on the Scottish island of Struay that you can almost smell the sea air and hear the Highland accents (which you will, if you read it aloud). Mairi Hedderwick’s Katie Morag books illustrate that some of the best children’s literature is that which is deeply rooted in particular places, created by authors who understand that where a story happens is nearly as important as what happens.

Published in 1984, “Katie Morag Delivers the Mail,” the first book in the series, establishes everything that makes these stories special. Katie Morag lives above her parents’ shop on Struay, helps with the mail delivery, and is known by everyone on the island (“our Katie Morag”). When she accidentally mixes up packages - handing out fishing hooks instead of gardening seeds, for example - the resulting mix-ups are bot amusing and utterly believable within the context of island life where everyone knows everyone else’s business.

What I love is how authentic the setting feels. I visited the Isle of Mull once several years ago, and it was incredible how familiar everything felt. This isn’t a romanticized version of Scottish lift designed for tourists or outsiders. Hedderwick lived on the Scottish island of Coll in the Inner Hebrides for decades, and her intimate knowledge shows in every detail. The shop stocks everything from groceries to fishing gear, because that’s how island shops work. The Oban Times sits in the post office, the actual local mainland newspaper for the Hebrides. The mail delivery is a social event, connecting people in isolated communities. The weather affects everything because on an island accessible only by boats, you’re always aware of the sea and sky.

Characters have names like Neilly Beag, with no pronunciation guide provided - Hedderwick trusts readers to encounter Scottish Gaelic naturally, the way Katie Morag does. In an era when Scottish culture has often been erased or reduced to tartan stereotypes, these books preserve genuine island life without explanation or apology.

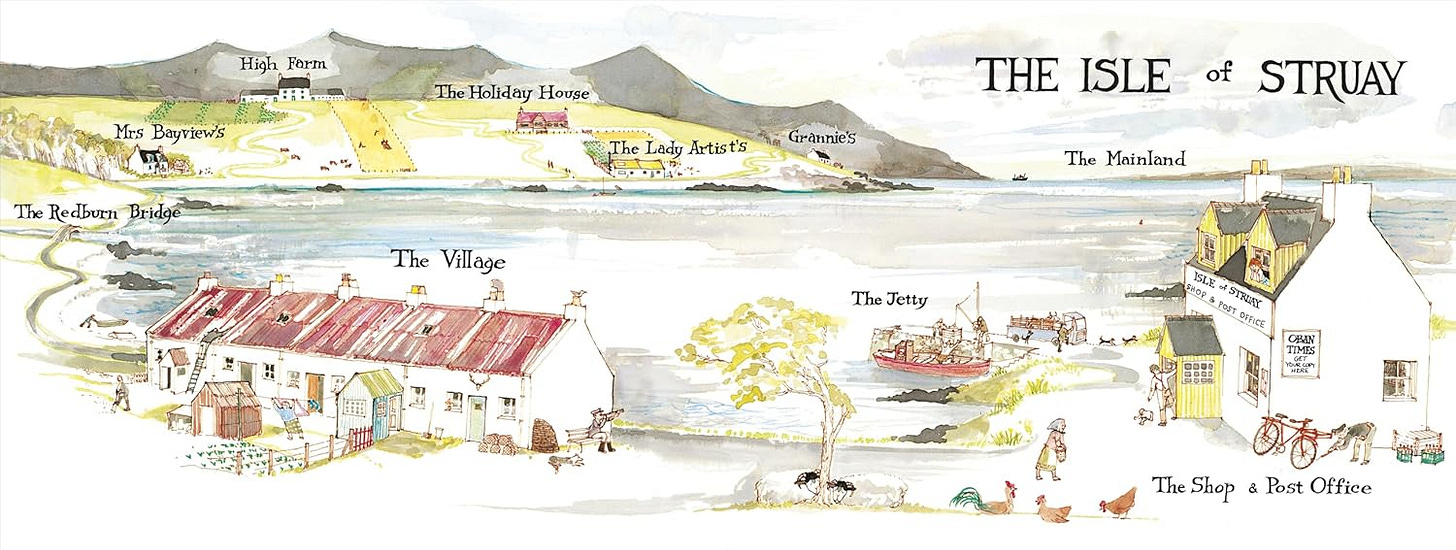

The island setting creates natural story constraints that work beautifully for children’s literature. Struay is small enough that Katie Morag can walk everywhere, large enough to contain multiple communities and personalities, and isolated enough that every character has significance. The map at the front of each book isn’t just decoration - it becomes part of the reading experince as children trace Katie Morag’s routes around the island, locating the scenes of her daily life.

Children understand bounded worlds like this - they live in them as well, whether it’s their neighborhood, their school, or their extended family. Hedderwick rewards careful readers with delightful details: covers of previous Katie Morag books appear as printed materials within later stories, and characters like Alecina the sheep reappear across multiple books, creating a sense of continuity and lived-in world.

One of my favorite parts occurs within the second book, “Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers.” One grandmother, Grannie Island, appears in the first book and we know her well. But here, Hedderwick introduces another grandmother, Grandma Mainland, and with that, gives us two grandmothers who each embody different approaches to island life. Grannie Island lives in a traditional cottage, grows her own vegetables (my toddler loves to point out the leeks), keeps chickens and sheep and goats, fixes her own tractor, and represents the old ways of island living. Grandma Mainland visits from the city with fancy dresses and modern conveniences (a hair dryer, hair curlers), bringing the outside world to Struay. Katie Morag moves between these two influences naturally, learning from both without the stories ever becoming heavy-handed about tradition versus modernity.

This is sophisticated character development disguised as simple storytelling. Katie Morag doesn’t have to choose between her grandmothers’ way of life - she absorbs what works from each, creating her own approach to being a young person on Struay (which is how Alecina the sheep ends up with curlers in her wool). The books respect children’s ability to navigate complex family dynamics and competing iinfluences without needing explicit guidance about which way is “right.”

Hedderwick’s illustrations support this authenticity perfectly. Her watercolors capture the particular light and landscape of Scottish islands - the way mist clings to hills, how the sea changes color with the weather, the distinctive architecture of island houses built to withstand wind and rain. These aren’t generic pastoral scenes, but specific depictions of a particular place with its own geography, climate, and culture.

The stories work partially because they trust children to be interested in authentic cultural details when they’re part of the story. Katie Morag participates in Show Day, helps her big boy cousins cut peat for the fire, combs the beach for driftwood and treasures after storms. The books never explain Scottish customs for outsiders - they simply present island life as Katie Morag experiences it, allowing readers to absorb cultural knowledge naturally through story.

I’m not normally one for television adaptations of favorite books, but I have a soft spot for the CBBC adaptation of the Katie Morag series, running from 2013 to 2017, and I find the adaptation demonstrates how well-realized the Struay world is. The series was filmed in the Hebrides, on the Isles of Lewis and Coll, and the adaptation feels seamless because Hedderwick had created such a complete, believable community that it translated perfectly to live action. Rare is the children's book series that can support this kind of expansion while maintaining its essential character.

What makes these books endure is their specificity. Katie Morag couldn’t live anywhere else and remain the same character. Her adventures grow naturally from island life - helping with the tourist season, dealing with supply deliveries, navigating the relationships that matter when your community is small and tightly connected. The stories feel both completely local and somehow universal, the way good literature often does.

In an era when much of children’s publishing aims for broad market appeal, the Katie Morag books remind us what we gain when authors write from deep knowledge of particular places and cultures. These books aren’t trying to teach children about Scotland - they’re books that happen to be Scottish, created by someone who understands that authentic setting enriches rather than limits storytelling.

Children respond to this authenticity even when the cultural details are unfamiliar (and even if their parents continually mispronounce Neilly Beag). They recognize truth when they encounter it, whether it's the dynamics of island postal delivery or the complex loyalties of family relationships. Katie Morag's world feels real because it is real, drawn from Hedderwick's lived experience and deep understanding of the place she chose to call home.

Next week: The perfect rhythm of repetition—and why some children's books are meant to be chanted, not just read.